#33 Out of the Box

Getting Banking Right, PIDF and LEI

I came across a different approach to banking this week, thought I’d share it with you guys. A lot of “experts” try to decode this complicated industry, with academics and industry veterans almost always having a different thought process.

Here’s a view from someone who had experience on both sides of the table.

Getting Banking Right

In this two-part series, Nachiket Mor (the guy who headed the committee that came out with the famous report that recommended the formation of payment banks, among other things) talks about the inherent problems with Indian banking.

In the first part, he argues that the “internal market” for banks is broken. Apparently this is the reason why a “young urban borrower can get a home loan at interest rates close to 10% per annum, but a middle-aged female rural borrower with an impeccable 15-year track record of repayment, pays more than 20% per annum for a much lower quantum of credit”.

To prove his point, he puts forward this data. As you can see, there is very little correlation between the lending/interest rate charged by banks (denoted by the yellow line) and the corresponding market rates (denoted by the deep blue line) or the underlying risks prevalent in the ecosystem (measured by NPAs, denoted by by the orange line).

So what’s the solution?

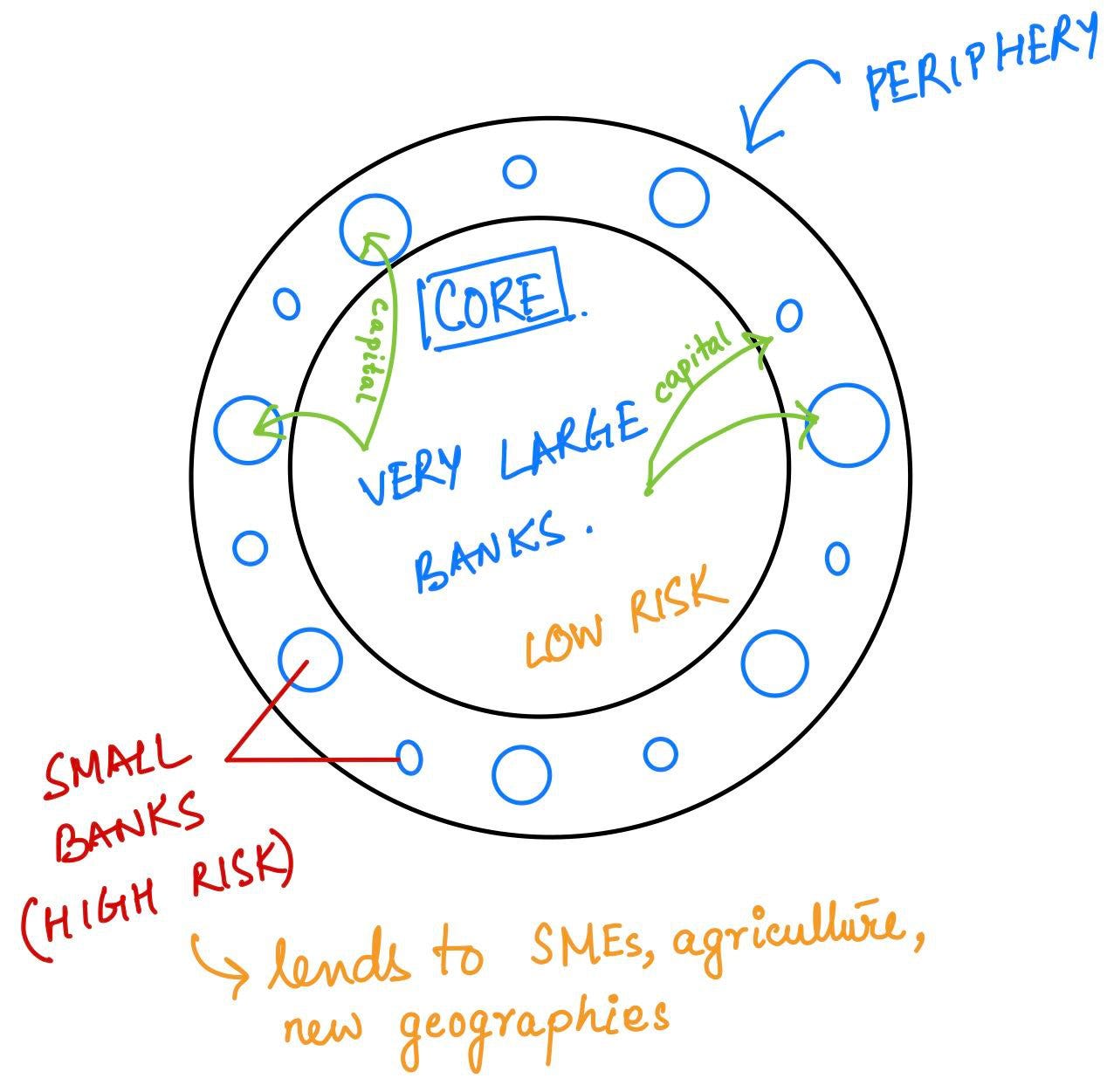

According to Nachiket, he proposes a multi-tier approach to risk-taking by banks: to simplify, very large banks takes on very little risk: only supplying capital to low-risk financial entities or to the bond markets, while smaller banks taking on larger risk, working at the periphery, kind of like this:

The second-part runs more into academia, but I’ve tried to capture the essence of it. Nachiket explains that despite enjoying the ability to offer deposit rates lower than what the government offers on it’s securities, Indian banks haven’t really been able to utilise the most from this low-cost deposits, mostly by misallocating capital. To quote,

“the best banks are ‘boring’ banks, whose strength is not embedded in the entrepreneurial quality of their leadership, and their technological prowess, but in the maturity of their embedded processes for managing their most scarce resource – capital.”

Again, to put it simply, removing the jargon - banks have access to huge chunks of retail deposits - money, that you and I put in the banks - instead of distributing this money (capital) in an efficient way in low-risk areas, banks choose to behave like venture capitalists by lending a large portion of it to singular institutions (corporates), thereby concentrating the risk to one large account.

To re-imagine the earlier illustration, very large banks at the core lend to the small banks who in turn, although exposed to risky individuals and mid-size corporates, lend only a small amount of capital, thus distributing the risk among a larger number of participants.

What is the counter-argument to this proposition?

Well, a journalist at ET now had actually pointed out the idealism in the original committee report I have referenced in the beginning - and I think her views can be extrapolated here as well.

According to her, banks are, at the end, commercial entities. Thus it may not be wise to assume that becoming “boring” is their top agenda. They will keep lending to those who they think are profitable, irrespective of the risk.

But is that really sustainable?

As Vivek Kaul highlights in his latest post, the bad loans problem is here to stay for a really long time. To quote,

“If we subtract the loans written off during 2019-20 (Rs 2,37,876 crore) from the overall bad loans of banks as of April 1, 2019 (Rs 9,15,355 crore), the bad loans as of March 31, 2020, should have stood at Rs 6,77,479 crore. But as we see they are actually at Rs 8,99,802 crore.

What has happened here? What accounts for the significant difference? Banks have accumulated fresh bad loans during the course of the year. The net fresh bad loans (fresh bad loans accumulated during the year minus reduction in bad loans) during 2019-20 stood at Rs 2,22,323 crore. Once this added to Rs 6,77,479 crore, we get Rs 8,99,802 crore, or the bad loans as of March 31, 2020.

This tells us that the bad loans problem of Indian banks hasn’t really gone anywhere. It is alive and kicking, unlike what many bankers, economists, India equity strategists and journalists, have been trying to tell us.”

“Alive and kicking” - two words that I would never like to associate with NPAs.

What’s up with RBI?

This week, RBI’s announcements will make us learn about two new terms - PIDF and LEI.

PIDF

On 1st January 2021, RBI operationalised the PIDF or the Payments Infrastructure Development Fund Scheme. The central bank had first announced this in six months ago, so here’s a recap from my June 6th post:

#1 RBI made an important announcement this week. It is going to create a Payments Infrastructure Development Fund (PIDF).

Corpus? ₹500 cr, half of which is going to be put up by RBI itself and the other half from banks and card networks.

Purpose? “to deploy Points of Sale (PoS) infrastructure (both physical and digital modes) in tier-3 to tier-6 centres & north eastern states.” PoS are those machines where you swipe your cards.

So why is RBI doing this? Because it is trying to push digital payments and remove the dependancy on cash.

There is some new information now that the scheme is live.

At first, it will be operational for three years and then extended by two years based on progress.

So how is the progress going to be measured? - It will aim to create 30 lac such touchpoint each year.

For reference, RBI actually tracks this data every month (with a three-four month lag) and the number of active POS devices in the country as on Oct-2020 are almost 54L. As on Oct-2019, that number was 48 lacs.

Hmm. That doesn’t sound right. How can RBI expect to install 30 lac new devices in a year when historically the growth has been in the range of 6 lacs? Well, that’s where the money comes in. Due to the high cost of installing and maintaining (and subsequently convincing merchants to actually use) these devices, turnovers below ₹10,000 per month aren’t really sustainable according to industry experts. This is why companies prefer to install these devices in major cities and towns only, leaving others behind.

Also, all 30 lacs devices aren’t in the physical form. It’s only 10 lacs (the rest can be digital - and even QR codes would be considered)

RBI will subsidise this cost (upto ₹250Cr) and ₹95Cr will be borne by card issuing network operators in the country.

If you’re thinking companies can just install a QR code, claim the subsidy and get away with it - well, that won’t cut it. There’s an “active status” criteria - The merchant needs to do either do 50 transactions in a period of 90 days.

Honestly, this is a great step towards financial inclusion and I really hope they meet at least half their target. I think even that’ll be a big boost in itself.

LEI

Starting April 1, 2021, all payment transactions undertaken by non-individuals to the tune of ₹50 crore and above using the RTGS/NEFT gateways will have to use the LEI or Legal Entity Identifier.

So what’s LEI?

To put it simply, it’s a 20-digit registration number that gives you the license to kill..err..process such large-value transactions.

Where can entities get these licenses?

Any Local Operating Units (LOUs) accredited by the Global Legal Entity Identifier Foundation (GLEIF), the body tasked to support the implementation and use of LEI.

Or you can directly get it from our very own CCIL which is the only body recognised as an issuer of LEI by the central bank.

Envisaged in 2011 after the 2008 crisis, the idea was this - Financial transactions are hard to track. Shady corporate entities have innumerable shell companies through which they bounce fraudulent transactions to escape taxes or jail. Some of these “fake” subsidiaries cross their own national borders, making it even more cumbersome to track. So a single, unique number was born to identify companies worldwide.

When you register for an LEI, you need to furnish all the details about your company so that easy answers can be obtained to difficult questions such as 'who is who’ and ‘who owns whom’.

Imagine X company in India routing a large-value transaction through Y subsidiary in Singapore. Someone sitting at Singapore can easily find details about X and Y just through the information contained in X’s LEI.

As of now, I only see people complaining that the threshold of ₹50 crore should be lowered so that more companies in India is brought under the ambit of LEI. What do you think?

That’s it for this week.

I love feedback. If you want me to cover a particular news, want to get featured, write a guest post or wanna simply say hi, do reach out to me at anirudha@bankonbasak.com or LinkedIN or Twitter. Meanwhile, like this post and share it around?

All views and opinions shared in this article and throughout this blog solely represent that of the author and not his employer. Since the author is employed by a bank, he has consciously chosen not to report any news related to his company to avoid conflicts of interest. All information shared here will contain source links to establish that the author is not sharing any material non-public information to his readers. His opinion or remarks on any news are based on the assumption that the source is genuine, thus he is not liable for any information that may turn out to be incorrect. This blog is purely for educational purposes and no part of it should be treated as investment advice. Using any portion of the article without context and proper authorisation will ensue legal action.