Hey everyone!

I can’t believe we’ve completed #50 issues! This also marks the one-year anniversary of the newsletter!

What initially started as a personal journal to keep track of banking updates, has grown into a community of over 3000 supporters! ❤️

Thank you so much everyone! Let's hope I get to keep doing this every week! 😁

What’s up with RBI?

This week, the central bank reviewed changes in fees and customer charges for ATMs and cash recycler machines across India.

From a customer standpoint, you’re going to face a teeny tiny increase in ATM transaction charges - from ₹20 to ₹21 (excluding taxes) starting January 1, 2022.

Note: This only applies once the customer crosses his free transaction limit - five if you transact from your own bank ATM and three if you transact from a different bank ATM (applies to metro cities; for non-metro cities - you get five free transactions in other bank ATMs as well)

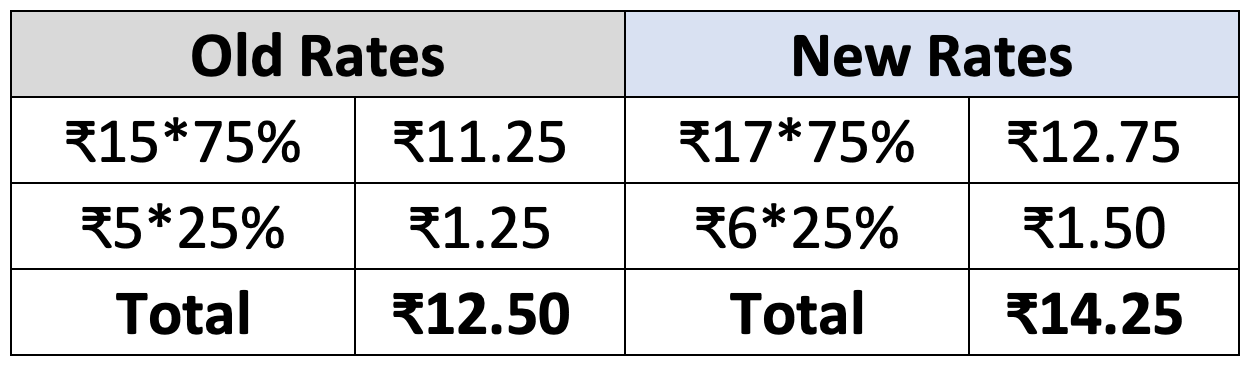

From a business perspective, interchange fee is set to rise from ₹15 to ₹17 for financial transactions and from ₹5 to ₹6 for non-financial transactions, starting August 1, 2021.

Now to understand both these changes, let’s go back in time. 🕒

A Bit of History

The very first ATM set up in India was in 1987 by HSBC, at Mumbai. Progress over the next few years was quite slow, with only about ~1500 new ATMs being set up in the next twelve years.

One of the primary reasons for this lagged growth was that ATMs functioned as individual independent entities. You could only use it if you had an account with that particular bank.

Then Came Switches

In 1997, Swadhan, the first network of shared ATMs (with inter-operable transactions) was established via the India Switch Company (ISC). Now, you could transact on any other ATM apart from your own bank, but with a fee.

By the time it got discontinued in 2003, it had connected over 1000 ATMs from 53 different banks.

As Swadhan became non-operational, other banks tried to make their own switch networks.

Public banks came together and formed CashTree.

Private banks came together and became part of Cashnet.

However, none of them could come close to what IDRBT (Institute for Development & Research in Banking Technology) achieved. It launched the NFS (National Financial Switch) in 2004 and within 5 years, its network had grown to connect ~50,000 ATMs consisting of 37 banks, emerging as the largest shared ATM network in the country.

It continued its growth after NPCI took over in 2009. As of April 2021, there were 1,181 members using the NFS network connected to more than 2.52 Lac ATM units (including cash deposit machines/recyclers).

What’s the issue?

That is quite the network. The industry must be growing at a healthy rate, right?

Wrong.

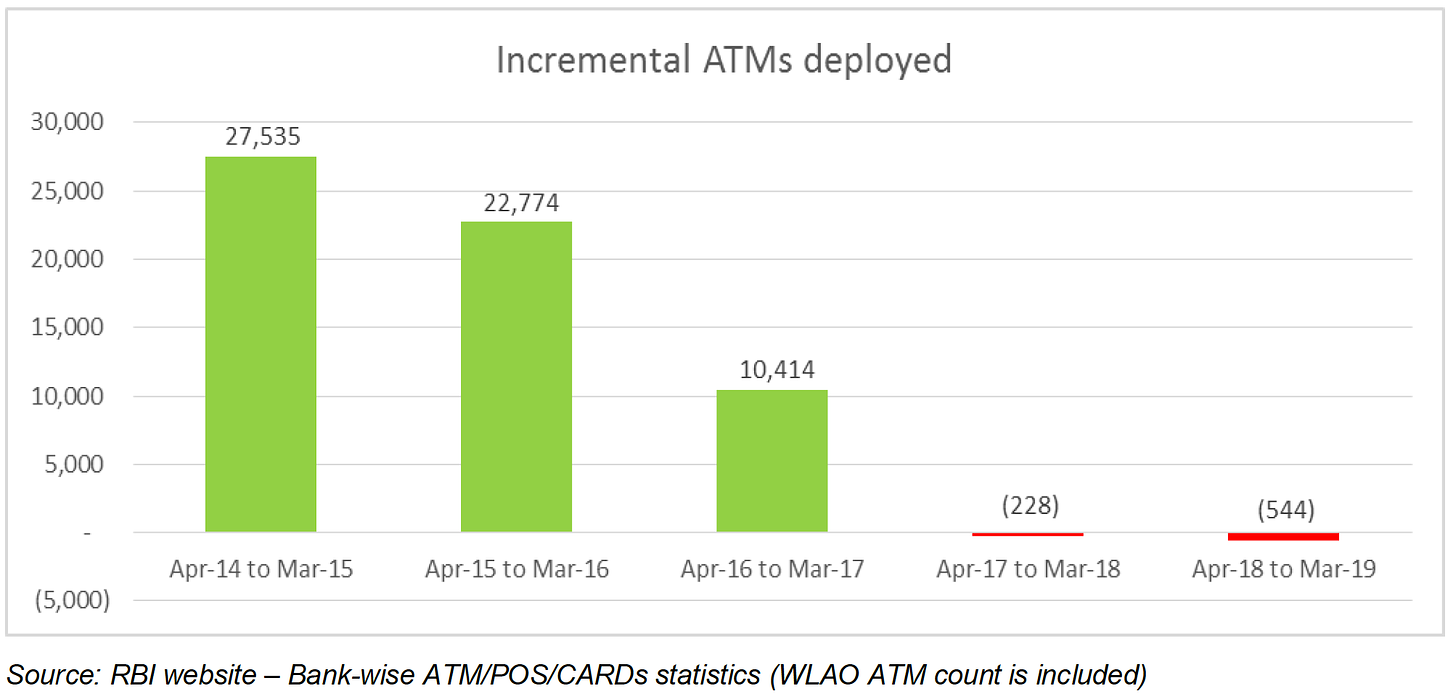

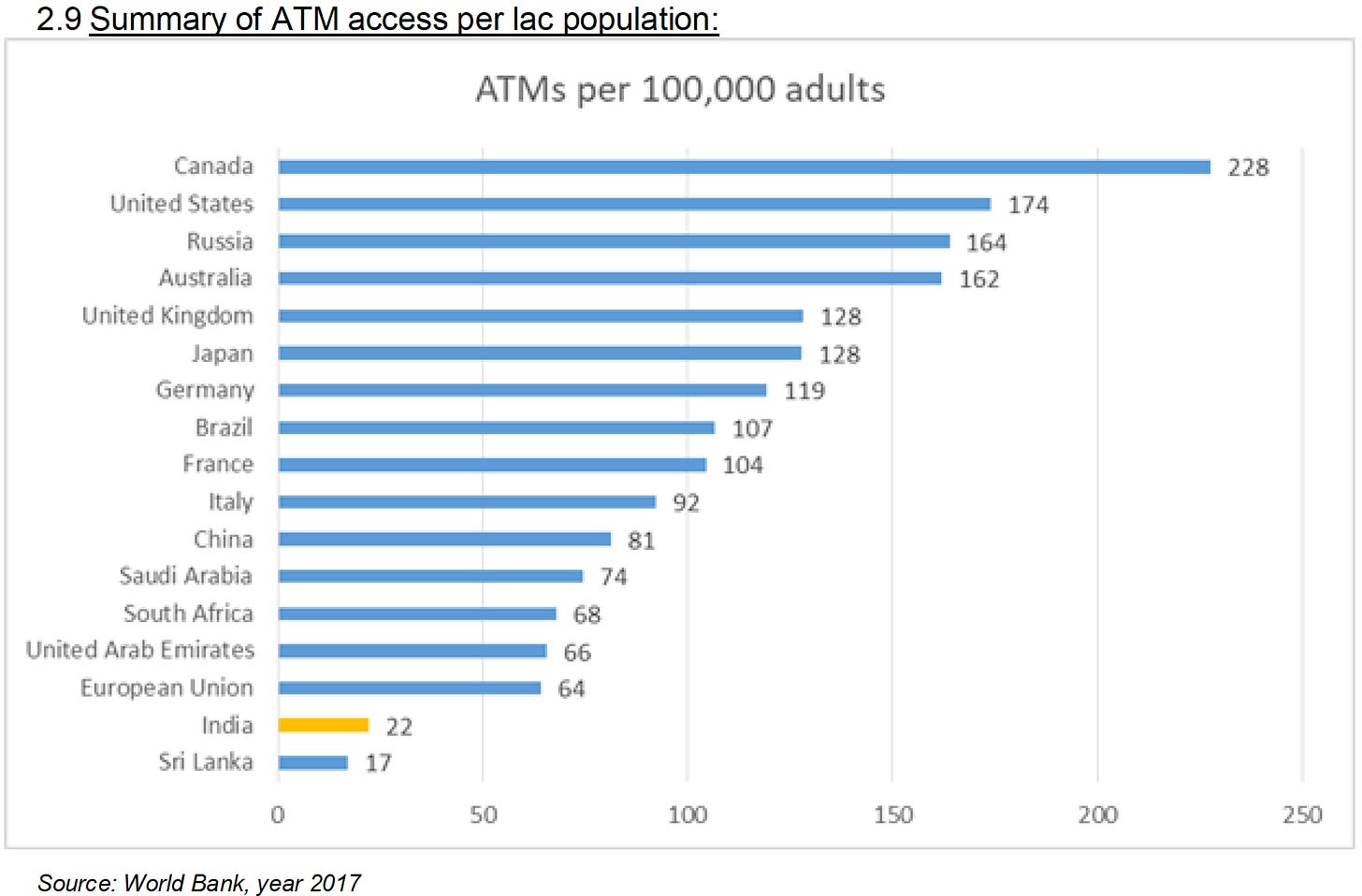

ATM growth has stagnated over the last couple of years. Its not that we have enough of them either. Compared to other emerging economies (China, Brazil, Russia, South Africa etc), India lags horribly behind.

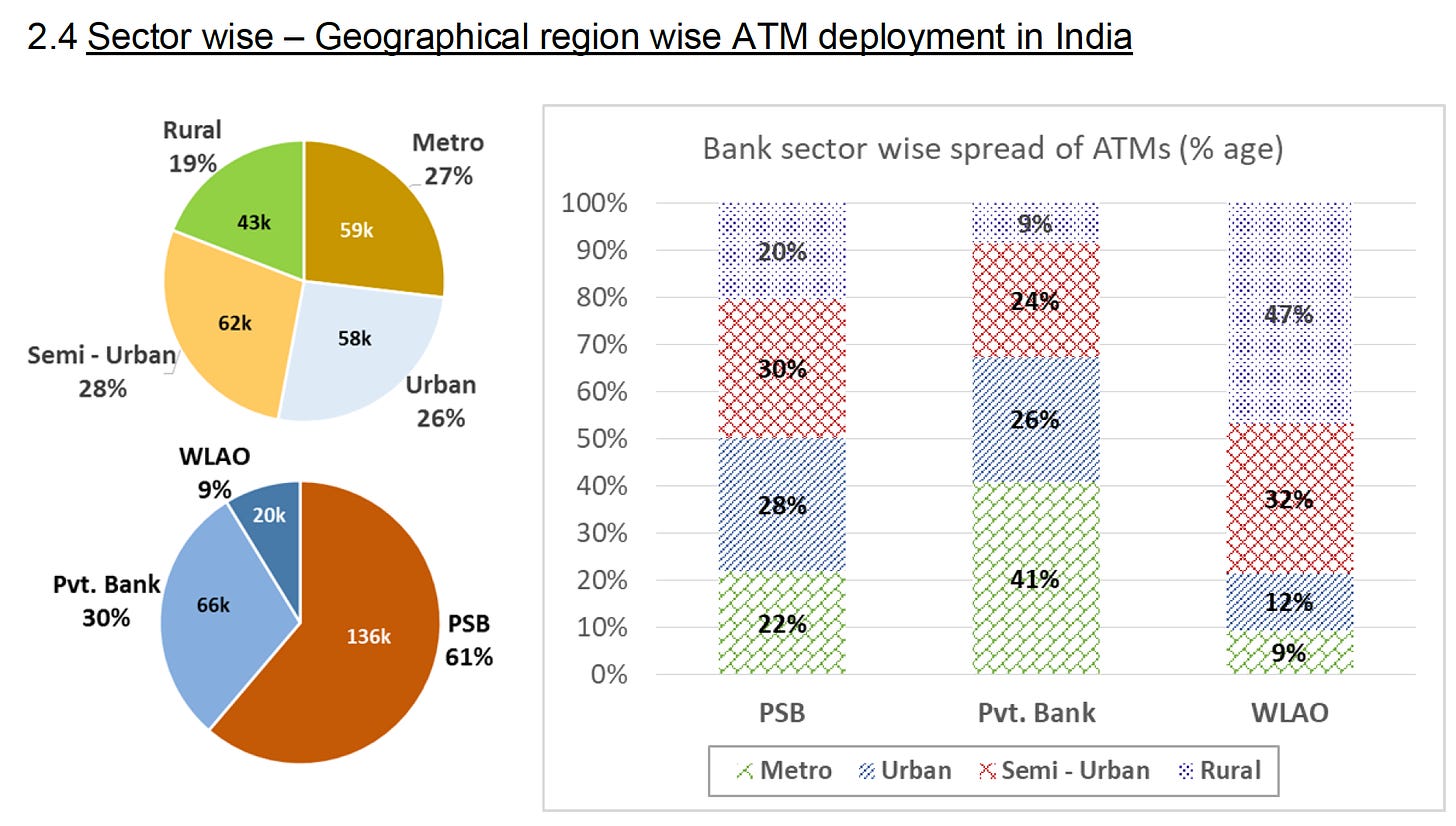

To top it off, the geographical spread of ATMs is skewed as well.

As you’d expect, more ATMs are deployed in urban areas (53%) when in fact, 70% of the population lies in rural areas.

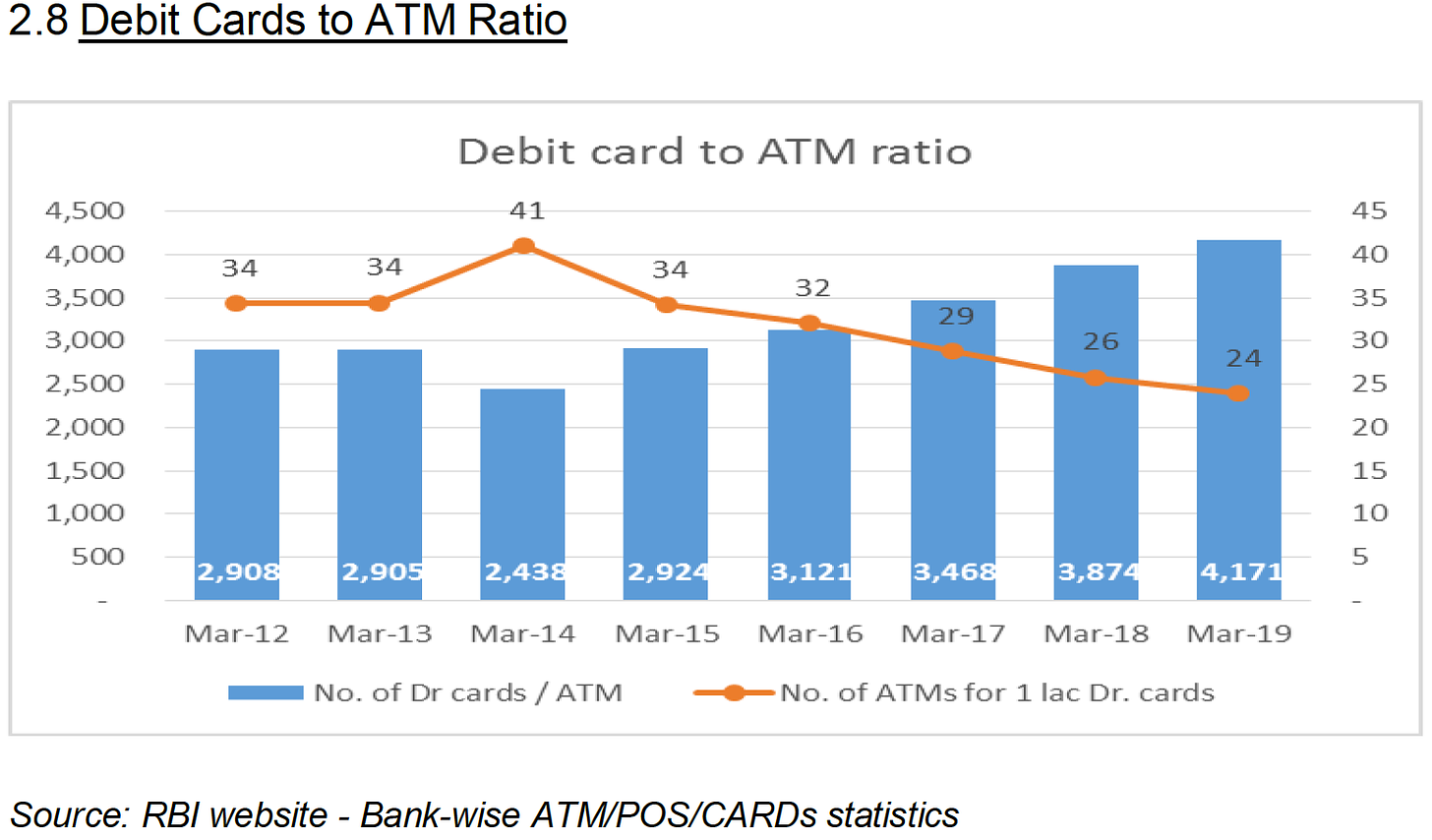

Another good metric to gauge the need of ATMs in a country is to measure the debit card to ATM ratio. As you can see below, this number has been constantly decreasing over the past couple of years, presumably due to the meteoric rise in PMJDY accounts. (As on June 2021, there are over 31 crore Rupay Debit Cards that has been issued along with the vanilla Jan Dhan accounts).

Why is this happening?

Mostly because of rising costs, coupled with the fact that the revenue structure hasn’t really been changed since 2014!

RBI finally woke up from its slumber in 2019, when it constituted a committee to review the changes in ATM fees and charges (yes, it forms a committee for everything!)

In 2020, the committee came out with a report, outlining all the suggested changes.

Finally, two days ago, RBI implemented some of them.

Will it move the needle?

To understand if RBI’s changes will make a difference, we first need to understand the unit economics of an ATM.

Now broadly, there are three types of ATMs:

Bank’s Own ATM: Initially, banks used to take all the headache of building (i.e. buying the hardware) and maintaining the ATM on its own. This made sense as long as banks could charge arbitrary amounts from customers of other banks (it went as high as ₹57 in some cases). To establish fair pricing standards, RBI capped the limits in 2008.

Brown Label ATM: With lower incentives, banks decided they’re better off outsourcing the headache to third party vendors. So now the hardware and lease is owned by a service provider but the cash management and connectivity to the network is maintained by the sponsor bank (who’s logo remains in the machine).

White Label ATM: To further the cause of financial inclusion, RBI introduced white-label ATMs in 2013. These are owned and operated by non-bank entities and they need not carry the logo of the sponsor bank(s) they’ve partnered with, but they’re bound by certain schemes set by the central bank (outlined below):

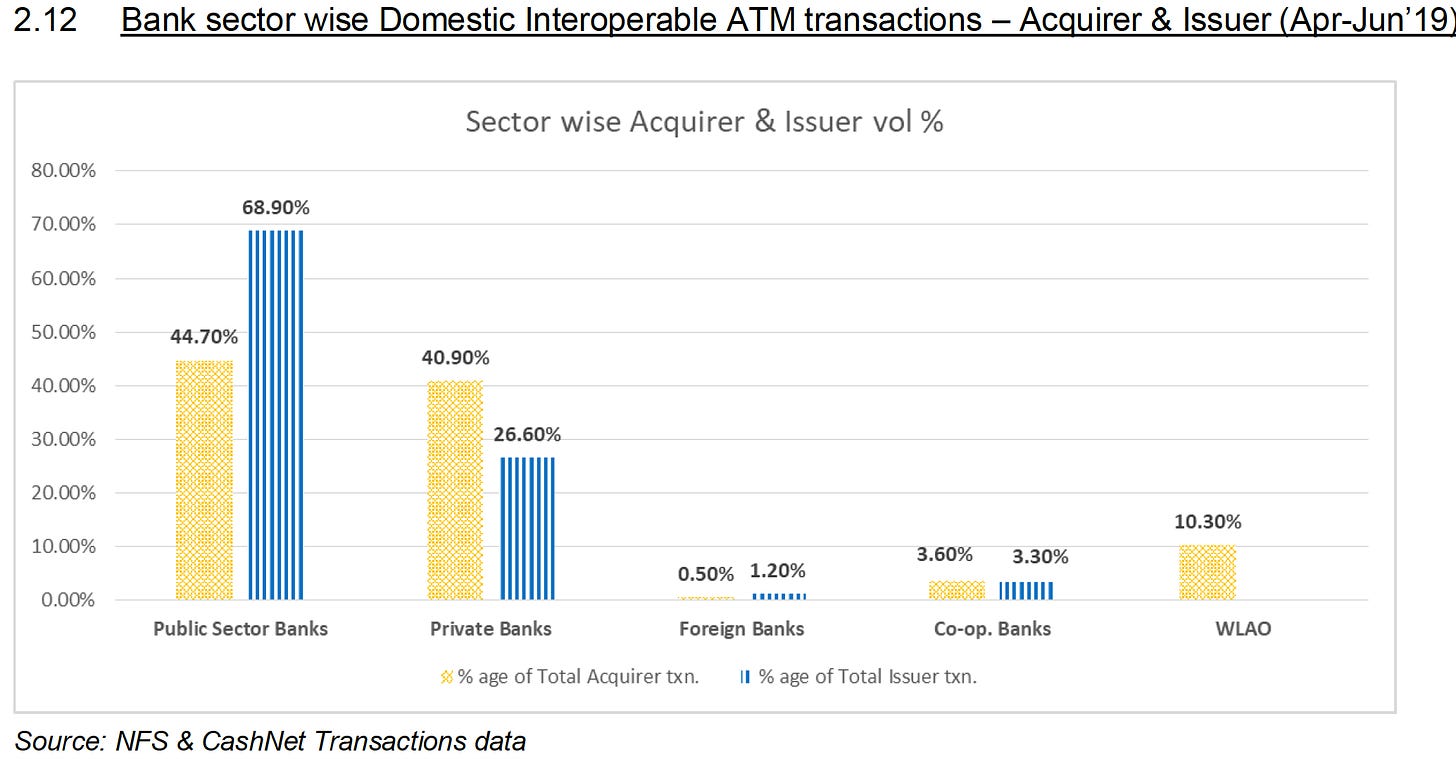

As you can see, the percentage of white-label ATMs (~10%) in the country is abysmal, indicating that it’s not really a viable business model for folks who are not in the business of banking. The only reason banks do it is to increase their brand presence, despite the costs.

What are the costs, really?

Each type of ATM has their own unique cost. For example, white-label operators have to pay an interest cost on the cash in their ATMs which is typically at a higher rate than what brown label and Bank’s own ATM are subject to.

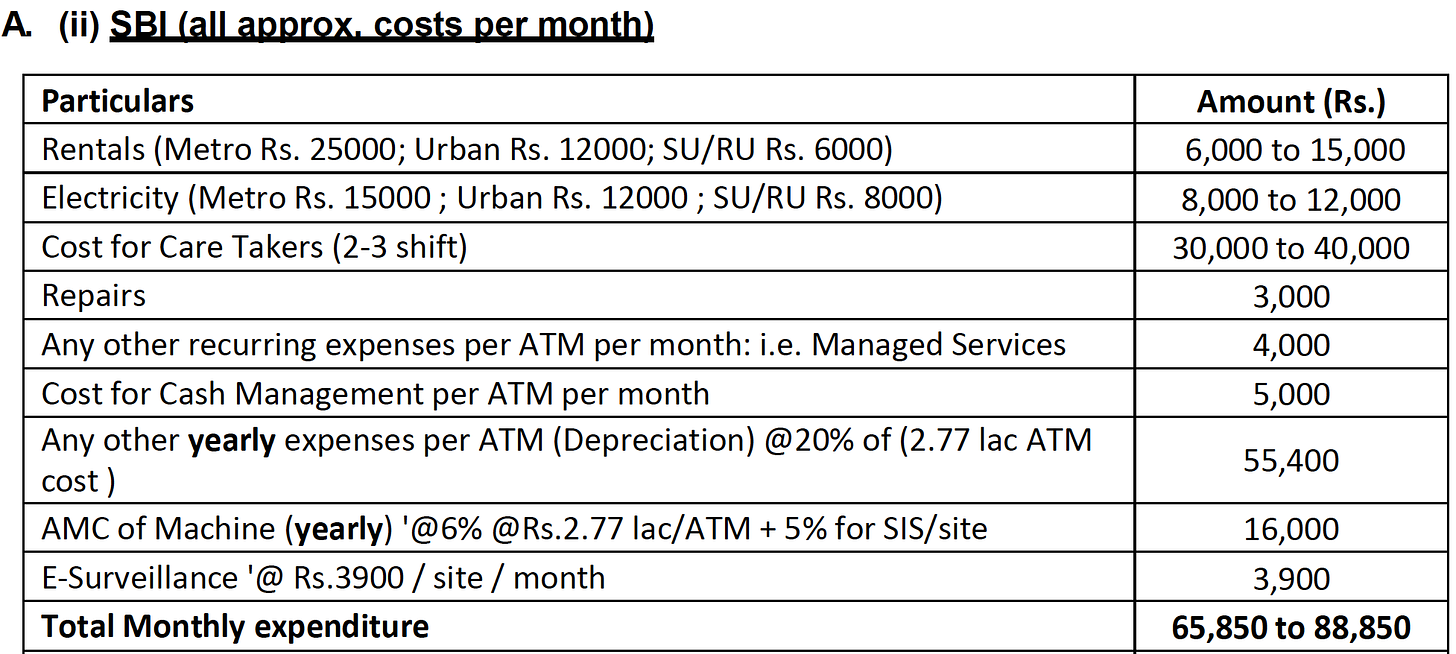

However, these differences are minor and it mostly boils down to rentals, surveillance, electricity and maintenance which forms bulk of the expenditure.

Here’s the cost structure of a typical SBI ATM, which has close to ~30% market share in ATMs.

Did you know? SBI spends roughly 7000 crore in ATM expenses every year. Also, their machines process over 1.3 crore transactions each day.

How does it earn?

Here again, there are certain revenue streams typical to a type of ATM. For example, white-label operators can earn a little extra through advertising other bank’s products which the others cannot do.

However, the broad sources of revenue are:

Interchange: This is the fee paid by Customer’s Bank (Issuer) to the Bank/white-label ATM operator (WLAO) who’s ATM is used by the Customer (Acquirer). For example, if you swipe your HDFC Bank Card at a SBI ATM, then HDFC will pay ₹17 to SBI (if you do a financial transaction, like withdrawing cash). The fees are lower (₹6) for non-financial transactions, such as PIN change, balance enquiry, etc. Interchange fee is divided between all stakeholders - banks and the brown/white label operator it has partnered with.

As of last week, these fees were ₹15 and ₹5 respectively. Do note that randomly increasing these fees doesn’t solve the problem for anyone. For example, it’s great if you are an acquirer. However, it’s not so great if majority of your transactions are issuer-based (i.e. you have to pay other banks/WLAOs) - like in the case of public bank ATMs (see below).

Note: WLAO do not have any issuer-based transactions as they are a non-bank entity.

Why are public banks net-issuers?

Because their rate of ATM deployment has lagged behind their rate of debit card issuance. Imagine this scenario. If more people have access to Bank of Baroda (a public bank) debit cards, but they hardly see a Bank of Baroda ATM nearby, they will obviously use the nearest ATM, which could be, say a ICICI Bank ATM. So each time you use it, Bank of Baroda will have to pay ICICI.

Another source of revenue for ATMs is

Customer fees: A bank can’t just keep paying interchange fees forever, is it? At some point, it needs to recover the cost from its customers, in the form of fees. After the initial five free transactions per month, banks are allowed to charge upto ₹21 for financial transactions (it was ₹20 earlier).

Often, banks lower or remove these fees in order to attract more customers. Take IDFC First Bank for example. Their Debit Card has unlimited free transactions across any ATM. You don’t see their ATMs quite often either (less than 600 across the country). So we can assume that most of their transactions are issuer based. As they’re not recovering it from customers, these costs are building on their books.

Unit Economics

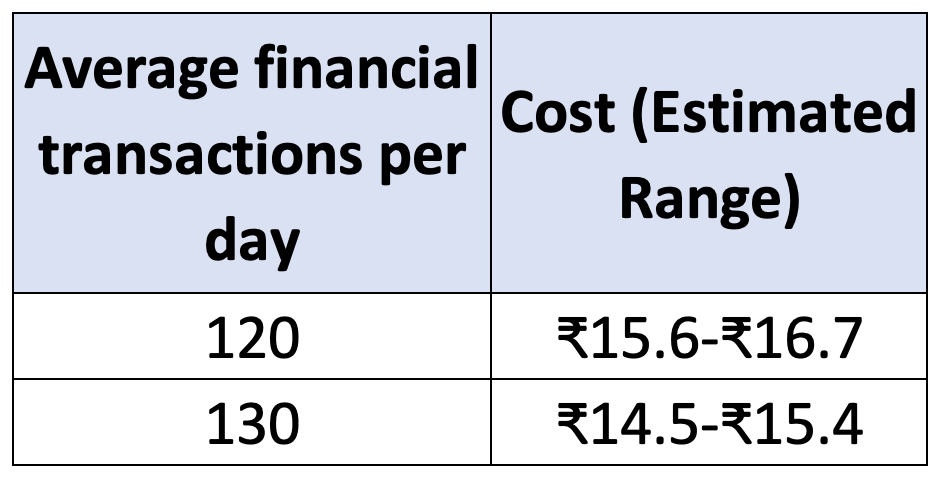

As per the committee’s report, the blended estimated cost (of financial and non-financial transaction ratio of 75:25) per transaction is:

As you can see, the costs keep decreasing as the number of transactions increase. This is why banks prefer to keep ATMs in high footfall areas, like banks and airports. WLAO have a hard time keeping up as they are mandated to install more machines in rural areas, where usage is low and thus, costs are higher.

Compare this to the old interchange rate ₹12.5 (blended cost of ₹15 for financial and ₹5 for non-financial txn.) - and you would understand that costs were definitely higher than revenue for a long time. With RBI’s change, it has gone up to ₹14.25, which isn’t the best, but at least it is more closer to the realistic scenario.

Let’s hope more WLAO are incentivised to install ATMs where it is needed.

If you want to get into this space, check out this website by Tata Communications, which is the largest WLAO player in India (their brand is known as Indicash). It has all the details about upfront costs and the monthly revenues you can expect if you do decide to be a franchisee.

Finally, why are we still talking about ATMs in 2021?

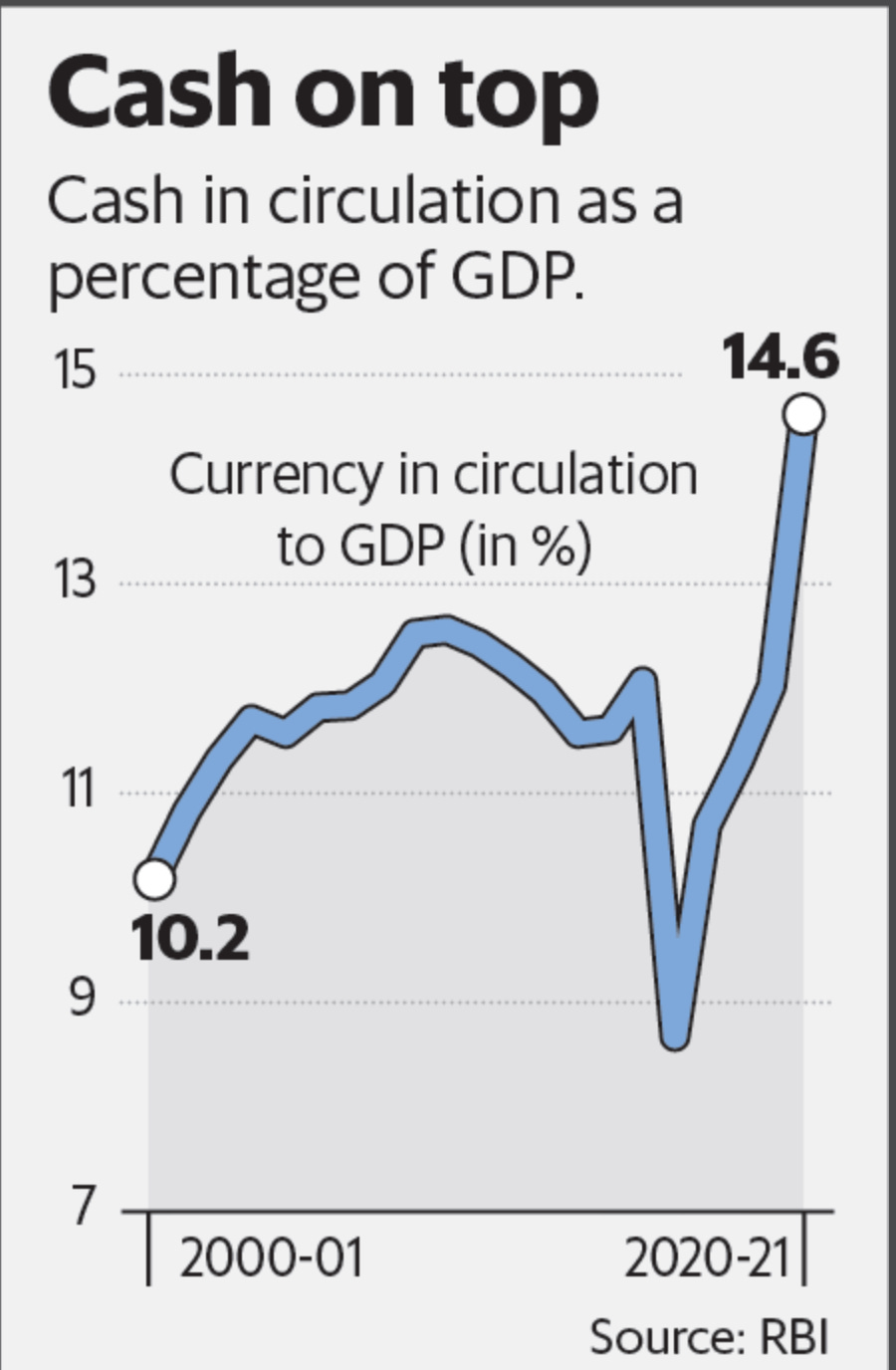

Despite all the talk about digital payments, cash still remains king in 2021, as is evidenced by cash in circulation reaching a two-decade high, even in absolute terms.

There could be multiple reasons for this - Covid has impermanently altered human behaviour towards cash - while some have shifted purely to digital modes to avoid handling cash, others have hoarded it for emergencies.

So instead of saying that the future of ATMs is bleak, we should rather concentrate in making it more efficient and also innovating it - so that all machines are self-sufficient, can act as 360 degree point of banking and provide other value-added services.

What do you think?

I love feedback. If you want me to cover a particular news, want to get featured, write a guest post or wanna simply say hi, do reach out to me at anirudha@bankonbasak.com or LinkedIN or Twitter. Meanwhile, like this post and share it around?

All views and opinions shared in this article and throughout this blog solely represent that of the author and not his employer. All information shared here will contain source links to establish that the author is not sharing any material non-public information to his readers. His opinion or remarks on any news are based on the assumption that the source is genuine; thus he is not liable for any information that may turn out to be incorrect. This blog is purely for educational purposes and no part of it should be treated as investment advice. Using any portion of the article without context and proper authorisation will ensue legal action.